For Bill and Lisa Roe, creating a home for eclectic, outsider music is a family business. After years of touring and releasing records on Goner Records in the garage punk band CoCoComa, the two settled in Chicago and started their label Trouble In Mind in 2009.

Whether it’s working with songwriter David Nance, of the Australian Indie-Rock band Dick Diver, or reissuing a long-lost psych classic from Del Shannon, the world that Bill and Lisa have cultivated with Trouble In Mind is varied in the way a well-rounded and well-respected record collection should be.

There is a lot on the horizon for the label. On Feb. 26, Trouble In Mind will release Nightshift’s new record Zöe and in late march, they will release the new album Chart For the Solution by Writing Squares. The label will also be releasing a new cassette run entitled the Explorers Series that features Brian Case of FACS, Nondimension and more.

We caught up with Bill Roe to talk about the label’s history, Chicago DIY, Sunwatchers’ incredible album artwork and one of the craziest demo submissions they have ever received.

What made you want to start the label in the beginning?

It was something that I personally had always wanted to do. I just never had the wherewithal or the money, really. I remember moving to Chicago when I did in the early ‘90s. I went to a party at this loft space for a label here called Underdog Records, which was a punk label. It was a house party and bands were playing.

I was chatting with this guy Doug [Ward of the Chicago band 8 Bark] who ran the label. He was telling me, “You know it’s interesting, you start being in the scene, going to shows to see your friends bands play. Then maybe your next step is you want to be in a band and you start playing shows. Then you’re like, ‘Oh now that I’m in a band and I’m going on tour, meeting all of these people, seeing all of these great bands. There’s this great band that nobody knows about them, then you want to start a label to release all of the music that you like. Then it just goes from there.’” So I’ve always had that in the back of my mind.

I’ve played in bands for decades. One day Lisa and I had been together for a while. She was pregnant with our daughter, this was 11 years ago now. Our band was on hiatus because she was pregnant. We had no idea what the future would hold. Maybe we won’t be able to be in a band any more? Who knows! We thought about it, and we thought “I think we can do this?”

It was a way to keep music around us. We didn’t want to lose sight of that. I sold my comic collection that I had been collecting since I was eight years old (laughs). We got a little slush fund, released a 7” and went from there.

The Chicago punk and indie rock scene of that era seemed so varied and separate from everything that was going on at that time. What was the scene like in Chicago when you started? Did you immediately feel at home when you moved there?

For sure! I came to Chicago from Weatherford, Texas, which is a smaller town just outside of Fort Worth. I came straight after high school. I graduated, hung out for the summer, and then moved to Chicago and started school.

Being a longtime music fan, I had already heard of a lot of Chicago bands. Touch & Go and Wax Trax, both of those labels were my go-tos for a longtime. I was like, “This town seems awesome… It’s a big city but it’s easy to get around.” So, this is where I decided to come.

I don’t know how old you are, I’m 46, but at that point the independent and underground music scene didn’t seem quite as fractured stylistically. At least to me. It wasn’t fractured in a bad way, but everybody had their own little camps. Those camps communicated and intermingled, but it does seem very separate. Moving to Chicago, back then everything seemed to be part of the same scene. Whether you were playing jazzy rock, punk, garage music, experimental, or noise — it was all a part of the “underground.”

Comparing Wax Trax to Touch & Go, you wouldn’t think that would make sense looking at it on paper…

Yeah, Wax Trax was industrial and dance music, and Touch & Go is like punk and a little bit of weird stuff. It wouldn’t have seemed like they would go together, but all of those scenes intermingled and hung out together. It wasn’t really a thing. For me, moving here wasn’t that big a deal. It just was what it was.

Not everyone is geared this way, but as a fan of music I sometimes gravitate towards checking out releases based on what label puts them out. Was that something you wanted to be conscious of starting out? Did you want to model Trouble in Mind after labels that you grew up with?

Well, in the certain sense that we wanted it to be something like where you see the label and be like “Oh, it’s on Trouble in Mind? They’re always great.” Even if it was something you never heard of you could read the description and go, “It’s on Trouble of Mind. Fuck it. It’s probably good.”

In the back of my mind, that’s what I had always hoped for. Where we could curate, for the lack of a better word, a discography and a reputation that people would view as solid.

I definitely did that. In my high school days, anything on Sub Pop I would buy. Anything on Touch & Go I would buy. Anything on Dischord Records, I would buy. Then moving here, it was like, “Flying Nun? Okay! Drag City? Of course.” It was just understood. It was going to be good or at least worth your time.

At what point did you start to see the label grow?

We were pretty fortunate in the beginning to have put out some singles by artists that would end up blowing up pretty quickly after that. We put out a pretty early Ty Segall single and of course he’s massive. We did a Fresh and Onlys single. We did a Limiñanas thing. We’re fortunate enough to have some artists who brought some attention to the label quickly. It seemed a lot easier than it should have been, I guess.

But that plays along to what I was talking about in the beginning. We had been in a band on a semi-reputable label. Goner is fairly respected in certain circles around the world. Our band had a reputation in that manner where bands could be like, “They were on Goner,” or “Yeah, we played with wherever and it was cool. Let’s put out a single with them, why not.”

Fostering these friendships and relationships with bands in different scenes and across the world really eased us into starting the label.

How big is the operation now? Is it still just the two of you?

It’s still the two of us! We run [Trouble in Mind] out of our house here over in the north westside of Chicago. One of our spare bedrooms is the label office and then we keep some stock in the basement too. Mailorder is run out of here. We do postal pickups almost daily.

We like to play it close to the chest. The label hardly makes any money at all. But whatever we do make, goes back into the label. We always are hearing new things and things that we’re interested in. We always want to keep putting things out. As much as I’d like to hire somebody or have an intern, it always ends up doing all of the work ourselves (laughs). It’s also one of those things where it’s hard to let go of your baby… I’m a little too anal rentative to have employees I guess (laughs).

How has it been being married and running a label together? You must feed off of each other’s enthusiasm so much.

We’re fortunate enough to be very comfortable in our relationship. We both love each other very much and trust each other implicitly. So, there’s no hangups. We were also in a band together, which is like the number one “no, no” that people always say when you’re in a relationship with someone. We respect each other and we acknowledge that we’re both rational, intelligent human beings to a certain degree. We trust each other. It’s just understood. So there’s that baseline there and having that worry off of the table just makes it easier to go for it.

As far as feeding off of each other’s enthusiasm and excitement, that still happens to this day. It just happened a few weeks ago actually with something that hopefully we’ll be putting out later this year… You just know. The hairs on the back of your neck just rise or something and you get that tingly feeling inside.

Is there a throughline for the kinds of bands or artists you would like to work with? Is there a specific Trouble in Mind “sound” or is it more just going with your gut?

Well, it is a lot of going with our gut. As far as finding the throughline — I don’t know if I’m the right person to ask about it — it all makes sense to us in our heads. If you were to come to our home and were to look through our record collection you’d say, “oh, yeah that makes sense.”

Everything that we listen to is the same kinds of things that we like to release. It’s a lot of jazz, psychedelic music, garage, punk, weird experimental stuff. I can’t say there’s a throughline. I hope there is. Sometimes those things don’t come into focus until you step back a little bit. Maybe someday after we’re long gone somebody will say it was perfectly obvious the whole time.

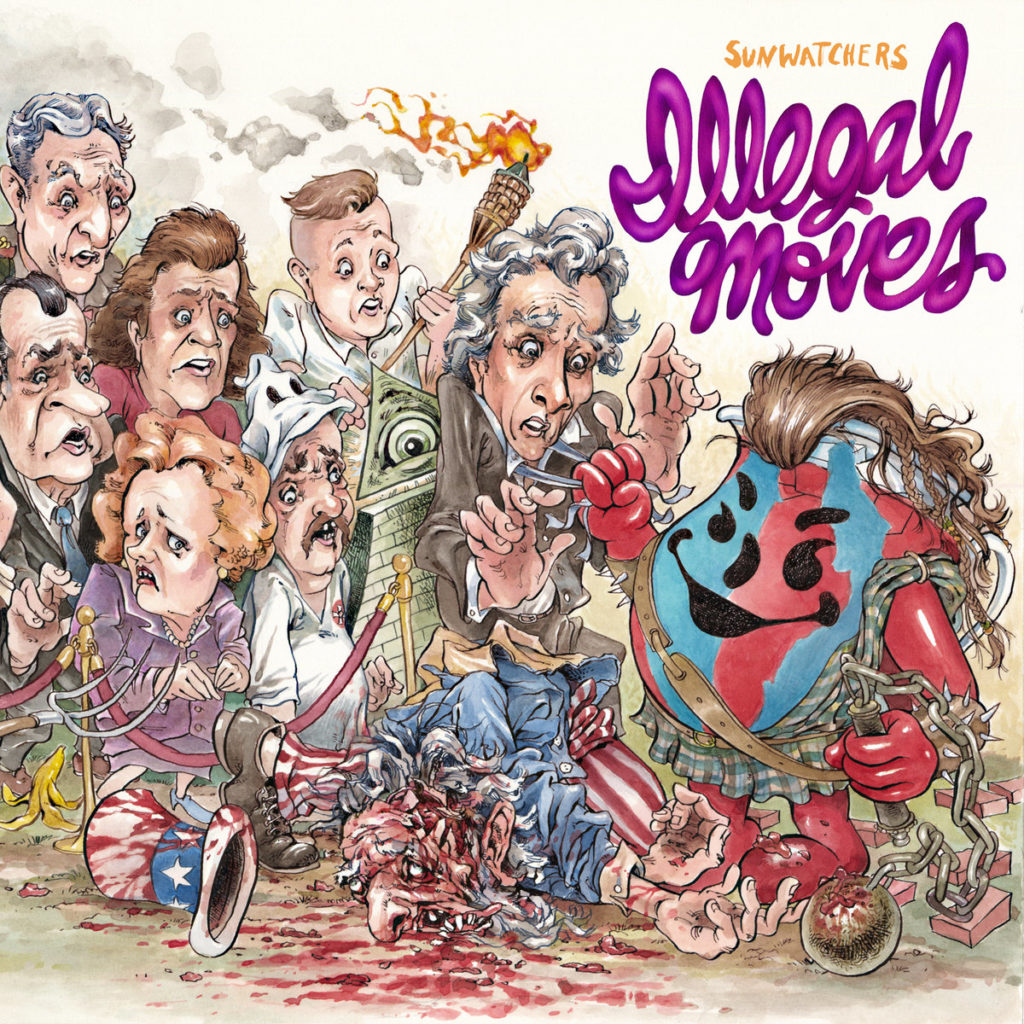

The album artwork for Sunwatchers’ Illegal Moves is one of the greatest things I have ever seen. Is there a good story behind that?

It’s insane. It was two years ago, I had gone to Goner Fest because Ethers and En Attendant Ana were both playing so I was there in Memphis. Sunwatchers didn’t play but they were on a little tour and they ended up playing at Third Man in Nashville the Sunday after Goner Fest. they were playing with that jazz ensemble Sons of Kemet. I thought, “this is the greatest double bill ever!” I hitched a ride to Nashville with a friend. I went to the show and it was amazing.

I was in the greenroom in the back and I was talking to the Sunwatchers guys. Jim [McHugh] was trying to explain to me what they were doing for the artwork. At that point, we were kind of behind schedule, everything was submitted except for the artwork. I was like, “Okay, let’s get this going…” He was like “He’s [artist Scott Lenhardt] working on it, it will be great I promise you.”

Now I’m like, “We really need to get this artwork going. Can you move it along?” Then he told me what was going on and explained the whole thing to me. Kool-Aid Man dressed as Braveheart and he’s fighting off capitalism, or whatever (laughs). I was like, “What? I don’t understand what’s happening. But okay.”

Then he sent it and I was like, “Oh … My … God.” We hadn’t even planned on making it a gatefold at that point but then I was like “we have to make this a gatefold to stretch across the whole record.”

It might be the greatest album cover I’ve ever seen.

It’s insane.

What was the most creative demo submission you’ve ever received?

You mean from a band trying to get signed to the label? (laughs) One comes to mind and I’m not going to name the band, but if they read this interview I guess they’ll figure it out. They didn’t end up getting signed to the label because it wasn’t our thing. They sent us a big box to our house. I was like “What in the world is this?” I opened the box and inside there was a baby doll that had been painted and redressed in weird clothes and a record in a sleeve. The record had been pasted over on the center labels with their own labels with our logo on it. Then they had done their own cover pasted on this record with our logo on the back [with a note written saying] “This could be us!”

There was a letter and a CD with the demo. I was like, “What is happening here? I don’t understand how you got our address?”

What are some of the biggest challenges the label is facing right now? Are you signing new artists? How has the business changed?

Well, I think probably the main thing that we’ve noticed is that bands that we work with can’t tour. That really hobbles them when it comes to income, and creatively. Because they can’t get together and jam. Being one person contained in your home, your brain just turns to mush.

That’s the thing. Our artists and bands can’t get out on the road and play to support themselves and the albums. It affects record sales. A band going on tour can help a record sell way more copies than it just getting released and having a few reviews pop up and that’s it. There are exceptions to all rules, of course. But that’s just a vital part of how this whole ecosystem works. You put a record out and then you go out on tour and everyone sees you then they buy the record and you keep repeating. You take away that aspect and what’s left is that we keep making records and hoping that people can find ways to buy them or to hear them.

For us, the bottom line is that we always want to try to help our artists and take care of them however we can. With those Bandcamp Days, Lisa and I had started talking about doing something like that in general and then when the Bandcamp Days came around we were like, “this is perfect.”

The first few, we were giving 100% of all sales to the bands during those first few months. It helped out people quite a bit and it felt good to do that. Now, we are giving any additional sales straight to the bands. That’s been the hardest part about the label for me. Our day to day is just me running it out of my house. I’m stuck in the house anyways. That aspect of it didn’t really change for me. But the effect that it’s had on our bands that we work with has been awful and I hate it.

So aside from offering an ear when people want to talk, text message until the wee hours and chat for the fun of it because I don’t want them to feel isolated … because a lot of the people we work with we have worked with a lot of them for many years. A lot of them that we don’t work with anymore, they’re still our friends. I still chat with Jack [Cooper] from Ultimate Painting everyday. He’s a friend even though we don’t work with him anymore. These people are like family to us. It’s hard.

This interview has been edited down for brevity and clarity.